Jean-Noël Herlin, a junk mail junkie Jean-Noël Herlin

20 January — 20 April 2024

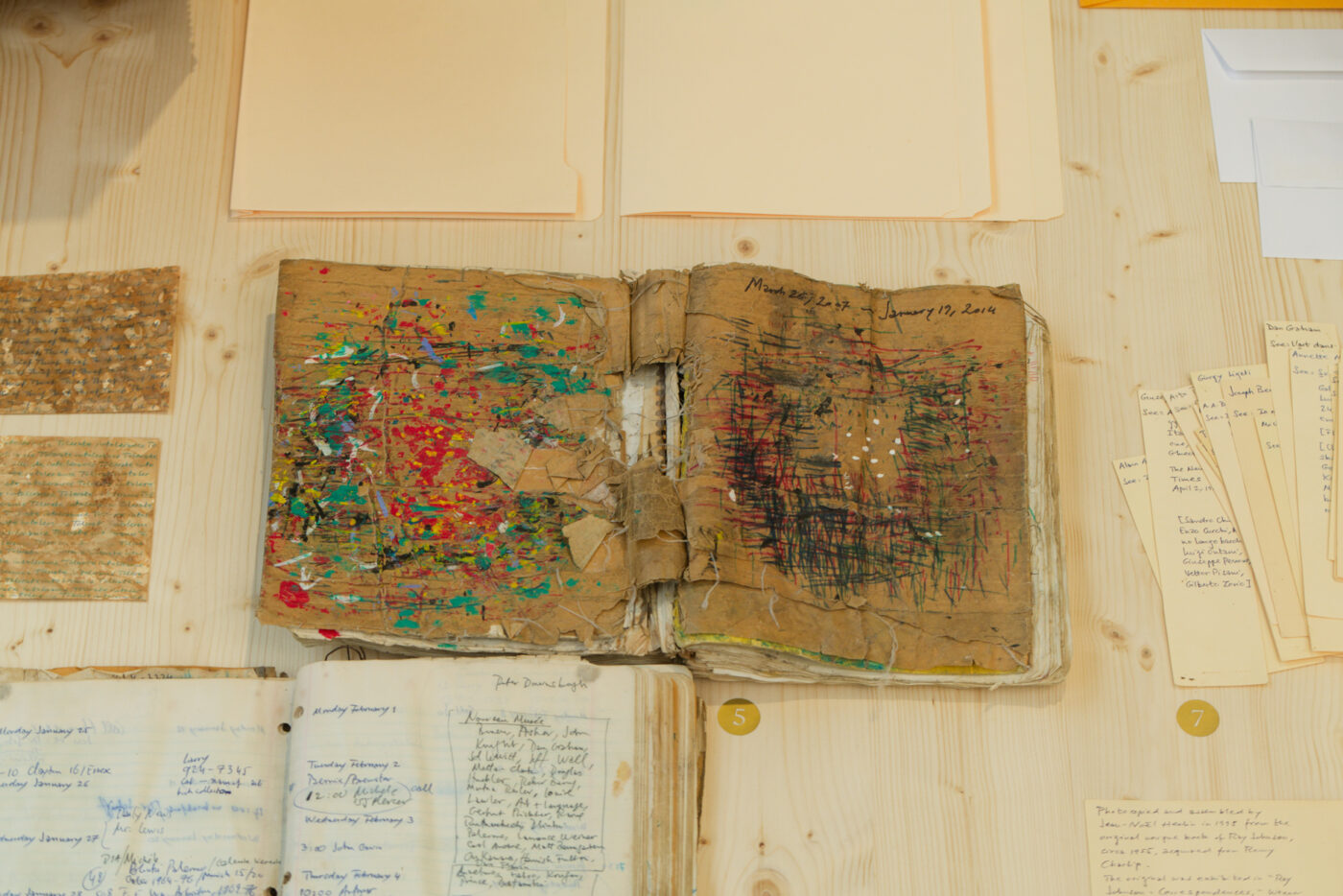

“When it comes to art, I am a junk mail junkie. Have been one for nearly thirty-five years. Well, thirty-four years to be exact, during which I have created an archive of some 300,000 items pertaining to the international visual and perfor- ming arts since 1950. If numbers speak, it contains material on more than 50,000 artists, runs 600 linear feet, and weighs five tons. A folly! A folly that has elicited ‘eternal gratitude’ from artists, scholars, and curators, and from others, glazed eyes and slack-jawed bafflement,” wrote Jean-Noël Herlin in 2007 in the introduc- tion to an article in Art on Paper, where he explains “how yesterday’s junk mail becomes today’s ephemera.”

Born in Paris in 1940, Herlin moved to New York in 1965, where he was active as a bookseller, archivist, and expert in all genres of modern and contemporary art. A voracious reader throughout his life, he considers printed matter as a “vehicle.” In his own work methods, he appropriates and hybridizes the artisanal approaches underpinning European book history and the artistic movements that emerged in the 1960s.

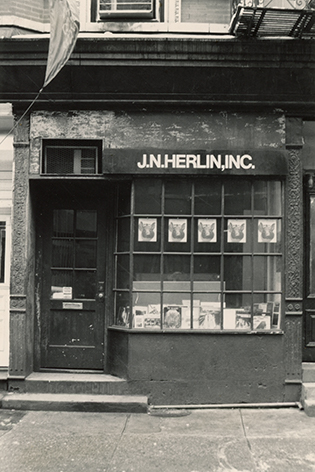

From 1966 onwards, he worked for Kraus Periodicals, a company specializing in the purchase and sale of periodicals and thematic book collections, which left a lasting mark in the history of bookselling in the second half of the twentieth cen- tury. In 1972, he founded J.N. Herlin, Inc., a pioneering antiquarian bookshop specialized in twentieth-century visual arts, performing arts, and film. Initially located in Greenwich Village, it moved to a loft at 108 West 28th Street and finally to SoHo, publishing nearly thirty catalogs or bookseller’s lists and organizing sixteen exhibitions along the way.

In 1973, as an extension of his bookselling activity, Herlin started what went on to become the Jean-Noël Herlin Archive Project, as part of which he collected and classified ephemera relating to modern and contemporary art: exhibition announcements, posters, press releases, brochures, press clippings, photographs, etc. As an attempt to encompass all forms of creativity, his “inclusive, panoramic, and non-hierarchical” archive, with its novel approach to so-called primary sources, is a critical contribution to an art-historical narrative that embraces a wide range of forms from different disciplines and manifestations. Since closing his bookshop in 1987, he has on numerous occasions been tasked with apprai- sing artworks and archives, notably with a view to their inclusion in institutional collections in the U.S.

In 2014, as part of my research, I in turn contacted Herlin asking for access to various files from the Archive Project. On this occasion, I discovered his unique, all-absorbing commitment to his work with written documents. Although he consciously situates himself outside the worlds of art and academia (among others by refusing to be recorded), I was able to persuade him to contribute to a film documenting his daily work, economy, and ideas.

In the course of our collaboration, in which we were joined by sound artist Cengiz Hartlap, it appeared that Herlin’s “writing practices” encompass broader notions than what the term “writing” might suggest. Some, like compiling an index or writing cross-reference cards, are a continuation of intellectual tech- niques introduced during the Renaissance. Others, such as exchanging or buying items of mail from art critics or artists that would otherwise have ended up in the trash (their junk mail, in effect), are archival inventions. Still others are common practice pushed to the extreme, such as handwriting bibliographic captions for each ephemera or assigning a price to the thousands of objects that populate artist Lil Picard’s overcrowded apartment. Others, finally, play with expectations, for instance when he turns his bookseller’s catalogs into erudite works of art ins- pired by Conceptual Art.

The first monographic exhibition devoted to Jean-Noël Herlin brings together a selection of five hundred documents and works, mainly from his personal archives, grouped according to his four main “writing practices”: reading/writing/ indexing, bookshop, archive, expertise. The presentation was conceived in conjunction with an immersive audio-visual installation whose scenario unfolds over eight hours and connects several threads: a day in the life of Herlin; the four sequences of his life’s journey in writing; events and encounters in New York and Paris. Following the different facets of his work, the exhibition reveals the com- plexity and sometimes unsettling implications of his radical commitment, which he himself describes as “utopian.”

Sara Martinetti

SOFARSOGOOD Sylvie Fanchon

4 May — 13 July 2024

From 3 May to 13 July 2024 at Bétonsalon

Opening: Friday, 3 May, from 4 pm to 9 pm

From 4 to 26 May 2024 at Pauline Perplexe, Arcueil

Opening: Saturday, 4 May, from 6 pm to 10 pm

Visit by appointment on Thursdays and Fridays: paulineperplexe@gmail.com

Open without appointments on Saturdays 11, 18, 25 May, and Sunday 26 May, from 2pm to 6pm

QUEPUISJEFAIREPOURVOUS is a protocol-based artwork by Sylvie Fanchon installed on the windows of Bétonsalon since 2021 and that is regularly updated, derived episodically and indiscriminately from among the ten phrases that compose it ¹. The words are those of Cortana, a “virtual assistant for personal productivity ²” equipped with a reflex-function that interrupts any unhelpful tangents undertaken by users, in a typically feminine voice. The artwork replicates this direct and unequivocal address, inscribing it on the glass facade of the art centre, transforming it in turn into a sounding board for services expressed in the first person in an easy-read style ³ with suspect motives. Located at the extremity of the building, the phrase is visible from the outside, but visible does not mean legible. Because each phrase, drawn in capital letters with no spaces or breathing room from one end to the other of the glass surface, traced in the margins on an invisible line, clearly stands out from the background wash of Meudon white, which has kept the imprint of the circular and regular gesture of its creation. In this way, the message has lost all its limpidity along the way: the meaning has difficulty resisting this collusion between the rectilinear line of the lettering and the agitated surface on which it is inscribed. This invitation to dialogue thus spins in an empty loop, which the gaze is invited not too linger for too long on, especially since all of this hides the disorder of the organisation (thus providing a real service).

These subtle discrepancies are prevalent in Sylvie Fanchon’s work, playing out through the inscription of a very clear symbol on a very simple surface. Extracting well-known and easily identifiable motifs, “common things” as she called them – everyday language, animal figures, decorative forms, or strips of tape – paring them down to retain only the contours and laying them in a strategic place (at the centre or the extremities) of a flat surface (a canvas or wall), using techniques with no particular knowledge required (collage, stripping, raking, whitewashing, etc.) and finally, revealing the strange character of this superposition, through the contrast of two colours that are often dissonant (red and green, pink and brown) attributed either to the form or the background… These are the well-known Fanchonian special effects that always manage rather mysteriously to thwart our immediate reflexes of recognition, to set our cursory associations into a tailspin, to create disjunctions, and elicit doubts, smiles, or laughs.

Although Sylvie Fanchon knew she had cancer, we actively prepared this exhibition together in Bétonsalon down to the finest detail. And on the occasion of a scenographic trial run, she latched onto a proposition for a rebound to Pauline Perplexe ⁴ that, this time, was intended to be improvised.

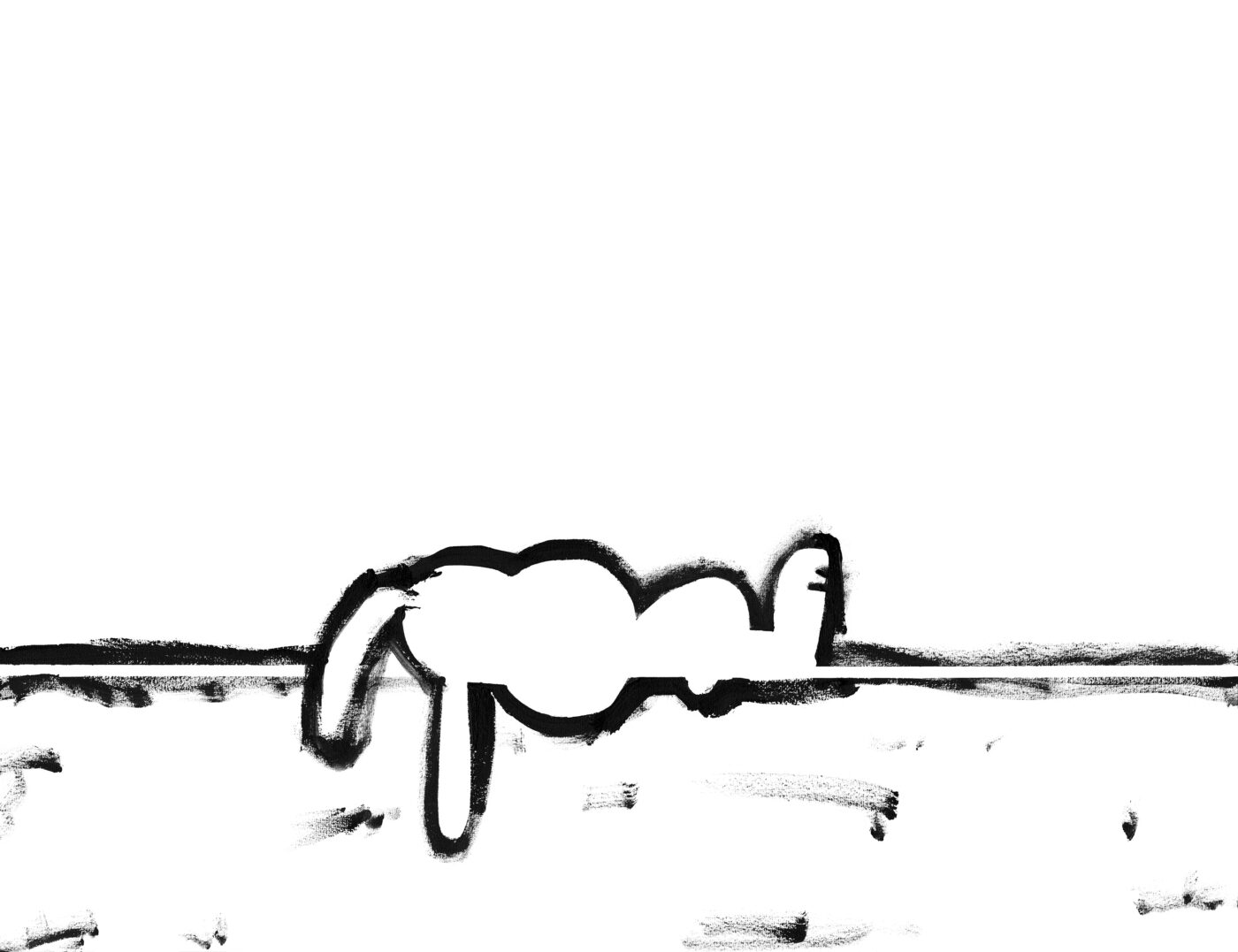

The exhibition at Bétonsalon brings together seven recent paintings, created between 2021 and 2023. On the five big canvases (130 x 200 cm) hanging in the exhibition space, we can read from left to right: Enter Password, Error Data Deletion, Clean Your Android, Do Not Turn Off The Computer, Wait. All of them confront alert messages – errors, loss of data, eternal waiting periods – addressed by computers to humans. The typical and mocking silhouettes of comic characters – like Toons ⁵ with an exalted Daffy Duck, Bugs Bunny kicking back with legs crossed, and also Snoopy asleep or inanimate – lying down or buttressing these messages in capital letters, floating in vast spaces that could be called voids (deep-space voids, windy voids, fiery voids) depending on the bichromatic interplays between backgrounds and figures: black on red or black on yellow or red on green… Sylvie Fanchon refused the illusionist space in painting – she has been known to say that a painting is a surface without depth, period – she nevertheless accorded the possibility that something like a sense of loss emerge from the dark depths of her recent paintings, a flip with a touch of humour or hope. Today, knowing the fatal result of her illness, we can rapidly assimilate these alert messages of the loss of computer data with loss of life.

The exhibition at Pauline Perplexe presents about twenty drawings. Some of the older ones compose festive games using linguistic signs, for instance when two empty bubbles come into contact in an attempt at amorous communication, and bear a strange resemblance to clouds or excrement, depending on the projective abilities of the viewers. Other more recent drawings react to a new kind of abuse of language, this time stemming from the medical register that Sylvie Fanchon must now face; that which, for a lack of better options, appeals to maintaining morale and staying active: “Keep Making Plans”, “Keep Your Spirit Up”, “The Show Must Go On”! The orders to stay positive from medical discourse, the dubious helpfulness of Cortana, and the anxiety-inducing urgency of computer messages all had the power to make Sylvie Fanchon angry. “Une ignoble inspiration me poussant ⁶” (Motivated by this ignoble inspiration), which she liked to quote from Marcel Broodthaers, this muted rage would set her to work.

The title of the exhibition at Bétonsalon, “SOFARSOGOOD”, follows an identical procedure in Cortana’s phrases: the text is applied in the margins in Meudon white, in a gesture that this time she intends to be chaotic, irregular, angry. The message is brief and its surface of application so broad that the letters are very big. That’s because this time the idea is to provoke a desire to stick one’s nose to the glass to discover the exhibition (rather than hide the disorderliness). In the face of cancer, SOFARSOGOOD resonated for us like a wager or at least a powerful wish, “so far so good” or “up until now, everything’s been fine”, which Sylvie Fanchon translated by “so far, so good”. This message already contains a hiatus, it is in fact an affirmation that is unsure of itself, an apt reflection of her work. Since Sylvie Fanchon is now dead, this double exhibition is a window that she has left open behind her.

Émilie Renard

I encounter the Angel in your ecstasy Klonaris/Thomadaki

26 September — 14 December 2024

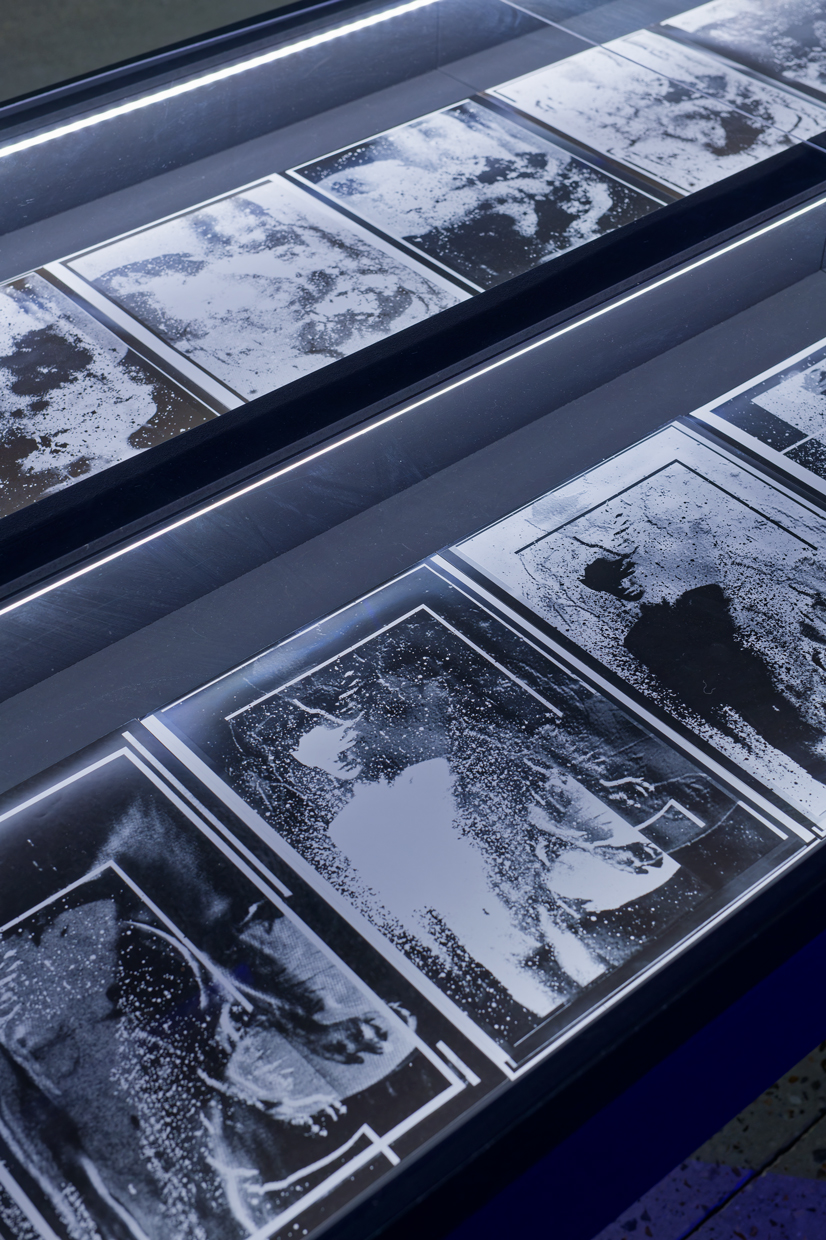

Since the 1970s, artists and filmmakers Maria Klonaris and Katerina Thomadaki have never ceased to break new paths and express their dissident positions, in hybrid, protean artworks abolishing the conventional boundaries between artistic media, cultures, and fields of knowledge. From the beginning, the artists have laid claim to a “double female authorship” proposing — in their Cinéma corporel — a “radical femininity” capable of “shattering all that weighs on it and constrains it”, beginning with the binary opposition of male and female. A concept further developed in their major cycles of works inspired by other “dissident bodies”: the Hermaphrodite (1982–90); the intersexual “Angel” (1985–2024); the conjoined twins (1995–2000). By revealing the power of these figures to transgress symbolic — as well as biological and anatomical — norms, Klonaris and Thomadaki have very early on contested the ideology of “nature” as a static order, thus anticipating current debates and theories concerning gender and the materiality of bodies.

Today, at Bétonsalon, a decade after the passing of Maria Klonaris, Katerina Thomadaki revisits and extends the Cycle de l’Ange [The Angel Cycle], which the two artists launched in 1985 and developed together over three decades. This vast ensemble of artworks, created in a variety of media — photography, video, sound, text, performance, installation — begins with a medical photograph: an intersexual person associated by the artists with the angel — a herald announcing the collapse of gender. In their artworks, the intersexual body is not reduced to an object of observation, pathologized by the medical gaze. On the contrary, the artists assert its multifarious and elusive character as it becomes the subject of infinite metamorphoses through multiple hybridisations with astronomical photographs. Betonsalon’s exhibition space is specifically transformed to welcome this “Angel”, who meets and dialogs with emblematic self-portraits of the two artists. Via their interventions on this “matrix image”, Klonaris/Thomadaki give shape to the infinite possibilities which open up once we overcome the binary regime of sexual difference. But while the “Angel” thus acquires a cosmic dimension, the two artists also express the genuine suffering experienced by the person stigmatised for their difference. This constantly reformulated image creates and maintains a certain tension between disaster and freedom, implosion and explosion, violence and emancipation.

Borrowed from the soundtrack of their expanded cinema performance Mystère II : Incendie de l’Ange [Mystery II: The Angel Ablaze], the exhibition’s title insists on the intensity of the relationship between the two artists and between them and this “Angel” who has long fascinated them. The reference to ecstasy highlights the way in which the amorous experience may overflow, undoing the limits between the self and the other — as well as between male and female, human and non-human, the imaginary and the tangible. Ecstasy also evokes the altered state which Klonaris/Thomadaki’s artworks seek to elicit in the viewer; the abandonment of a day-time regime of perception, governed by functionality and rationality, in favour of a nocturnal plunge into a world both political and eminently poetic.

This exhibition is part of a long-term research project supported by Bétonsalon with Maud Jacquin on Klonaris/Thomadaki’s œuvre, considered through the lens of performance and its relationship to gender and identity issues.

Upcoming